Explaining climate inaction

Facts: moral disengagement -> climate inaction 🤷🏻✈️ | Feelings: Climate excluded 😩🧱 | Action: Make it easy to say YES! 🧈👍🏽

Hi from the train to Paris! I’m on my EuroTour 2023 to Paris, Brussels & Exeter. Get in touch if I’m coming to your city and you want to host a talk or book club!

Before we dive in, a quick practical note on We Can Fix It (the awesome climate advice newsletter from me, climate scientist Kim Nicholas, that you’re reading right now).

Recently, a bunch of readers have told me they want to support my work here, and generously pledged their financial support for We Can Fix It. Thank you!!!

I’ve decided I’m activating the option to accept reader payments. Let me explain why.

I’ve been writing this newsletter for almost 3 years, for free. It’s a labor of love to get actionable, evidence-based climate advice out in the world.

A reader, Daniel, wrote me this week about “the team at wecanfixit.substack.com,” but this Substack is 100% made by me! Each issue takes me 10+ hours of work to plan, research, write, edit, fact-check, design, publish, and share. (Shout out to my talented friends Cara and Emma who’ve donated their design skills for the logo and a figure, respectively. <3)

I would love to expand the work I’m doing here, and I have tons of ideas for ways to make it better, but I don’t have the capacity to make it happen as a solo volunteer.

If you find this Substack valuable, and if you are in a position to financially support it, I would be honored if you click the button below to become a paid subscriber. If you’re not, no stress. Thank you!!

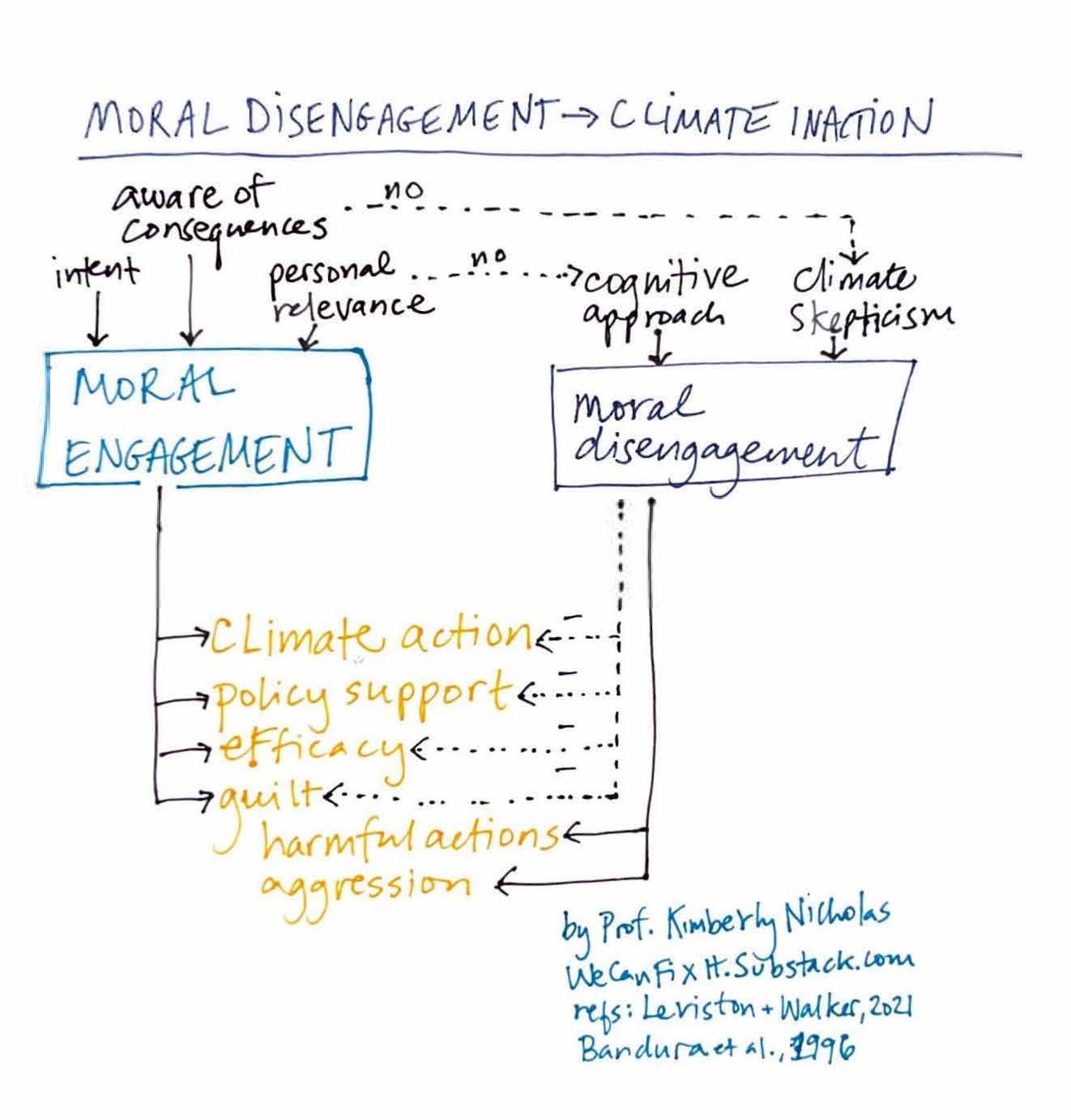

Moral disengagement → climate inaction

Why don’t more people act on climate?

One reason may be moral disengagement—treating climate change like a distant problem for other people to solve, using one of eight mechanisms to reduce one’s own feelings of guilt. Moral disengagement also reduces efficacy (ability to act) and climate action—in your own lifestyle, and in political engagement. And it can be used to rationalize and uphold climate inaction (like not participating as a climate citizen) and harmful behavior (like continuing luxury emissions).

That’s my quick summary of a research field dating back to the 1990s. Moral disengagement theory grew out of Bandura’s social cognitive theory, which holds that moral standards can shape behavior. Basically, people want to be moral. They use morals to assess their own actions as right or wrong; acting in line with morals increases self-esteem and social acceptance.

Here I’m drawing especially on a classic psychology paper by Bandura and colleagues from 1996, and a recent paper on moral disengagement and climate change by two Australian psychologists, Zoe Leviston and Iain Walker. As they write, understanding how climate change is moralized matters, because:

“Political debate about climate change and the need to act remains rooted in moral discourses.” – Zoe Leviston and Iain Walker

How moral engagement increases climate action

To consider an action a moral issue, you need intent (you did it on purpose) and awareness of its consequences. You also need to consider the issue personally relevant.

The Australian study found that increased moral engagement increased a sense of efficacy (“I matter”, “Individuals matter,”) and responsibility, and increased climate action— from decreasing driving to joining climate movements. It also increased a sense of guilt, which may play a role in driving these behaviors.

On the other hand, moral disengagement decreases all the good stuff: climate action, a sense of efficacy. But it decreases guilt, which the theory’s founder hypothesized was one of its main purposes. (The original 1996 study found moral disengagement increases harmful actions and aggression. Like the world needs more of that…!)

Now, how do people wiggle out of a moral framing?

8 mechanisms for moral disengagement, with climate examples

1. Justification: “The ends justify the means.” “There was an economic benefit, so the climate harm doesn’t matter.”

2. Advantageous comparison: “Exxon/Elon is worse.” “It’s the lesser of two evils.”

3. Euphemistic labelling: think “green flying,” “carbon neutral.” Basically greenwashing to make things sound less harmful.

4. Minimize, ignore, distort the harm caused: “This is just a drop in the bucket.” “Climate change isn’t such a big problem.”

5. Displace responsibility: Point the finger at others to diminish your own accountability. “Leaders are more responsible than me,” so I don’t have to do anything.

6. Diffuse responsibility: “Change the system; everyone is responsible,” so no one feels responsible. Obscure the consequences of your own actions.

7. Dehumanize: “’Those people’ aren’t like us.” Create distance from others to diminish their value.

8. Blame the victim: “Greta is just in it for the money.” Increase the social stigma of the marginalized or most impacted to justify their suffering.

Sound familiar? Watch out for moral disengagement in conversations and media— it’s supporting climate inaction! We’ll keep building up the personal relevance and moral engagement here— I’ll write more about how to face these arguments in a future post.

Feelings: Climate excluded

I heard a really interesting reader perspective I want to share with you:

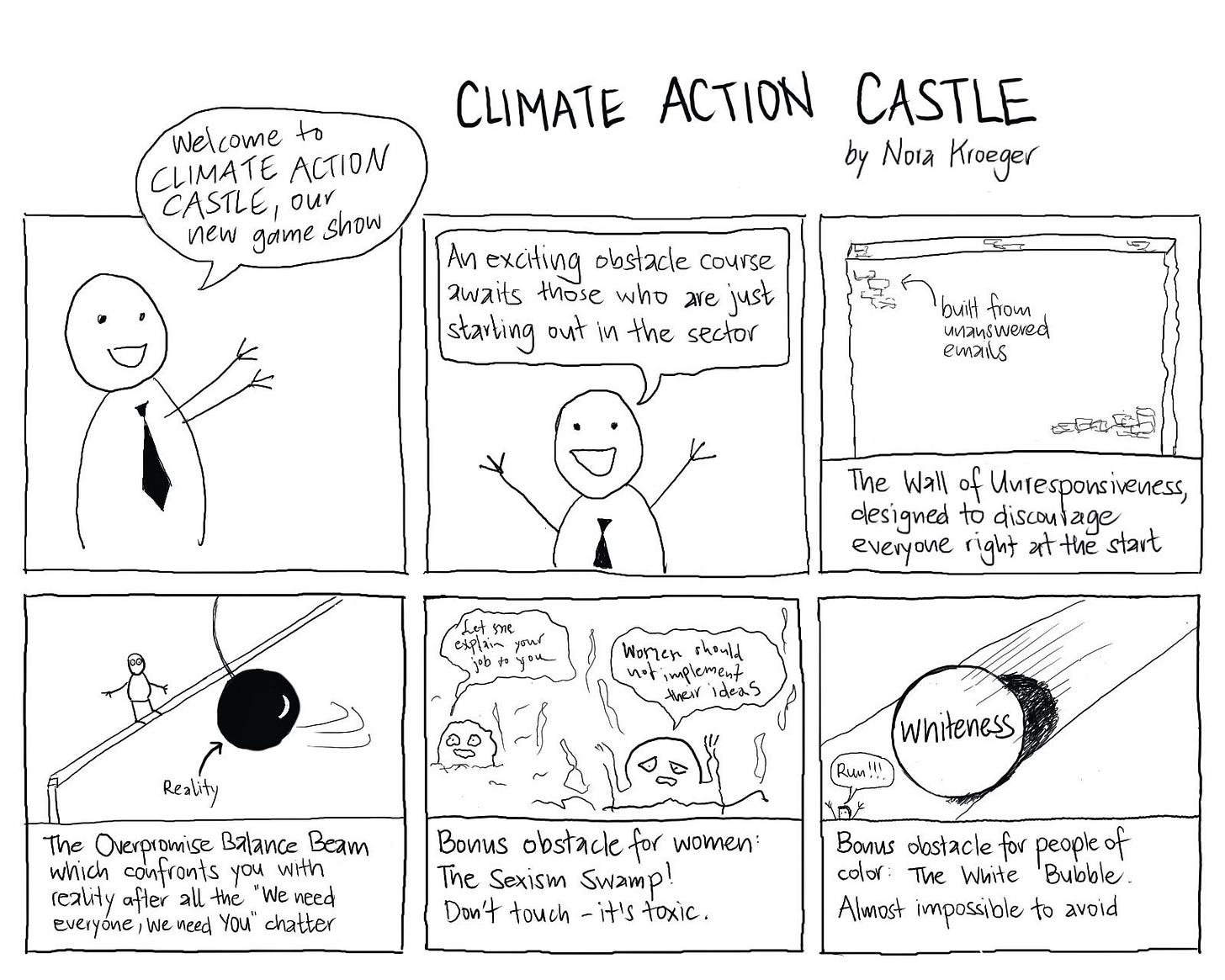

“I started dedicated climate work and volunteering last year, and - I can only speak for myself here - it was not as easy as many people make it sound.

Making connections was harder than I thought, getting support was harder than I thought. Just getting an email back was harder than I thought.

Now, maybe this is not supposed to be easy. And no one owes anyone any connections or support.

But when a movement or a sector says "We need all of you, just get involved" and then makes the "getting involved" part feel very difficult, I think something is off. Expectations are being set that are not met.”

For ages, climate people have been working hard to expand the circle of “people who potentially care” to “people who care + are doing useful work.” A lot of folks have gotten the message, “Hey we need you! Please join in, show up, roll up your sleeves!” And they’re heeding that call, and trying to jump in, which is SO great!

But it can be tough to get started. How do you find the right group for you? (Refresher: “Find your Climate Peeps” from Sept 2021!) How do you align your skills to contribute once you find them?

It’s super concerning to hear people have not felt welcomed, found it difficult to break in to a climate group, or even not heard back at all after several attempts. This is a lot of lost energy, creativity, and capacity that the climate movement desperately needs.

This experience Nora brought up inspired this month’s climate action, which is…

Action: Make it easy to say YES!

Here are two things that are sometimes at odds with each other in climate action:

We need to help each other, ask for help when we need it, draw on each others’ strengths, learn from each other, share the load…

YES, AND we need to support a sustainable working culture, not glorify overwork, respect others’ boundaries and not set unreasonable demands on their time.

SO, how can the new folks who want to learn, contribute, and find their place (yay!!) get the support they need…

WITHOUT burning out the too-few people already neck-deep in the climate work they’re desperately trying to get done? It takes a lot of time and energy to welcome and guide new folks and bring them up to speed. Often that process can be super rewarding and fun. But sometimes, it can be a one-way drain to try to bounce between too many demands that don’t end up going anywhere.

Nora’s post made me think about the requests I get for my time. I do not have capacity to say yes to them all. What makes it easy for me to respond immediately and to say YES? What does not make it easy for me to respond — and therefore maybe ends up unanswered in my Inbox 4,784 that horrifies my Inbox Zero friends?? I’m doing my best, but I definitely drop some balls, which I feel bad about.

With that in mind, here’s this month’s action:

How to get people you don’t already know to answer your emails!

Especially when you’re asking them for something. I think this skill could come in super handy in building climate community and new connection— and if done well, save us all a lot of time and stress.

Something I didn't realize until it happened to me: even if you’re reaching out to someone with a lovely offer, like “Can I help you?”, it requires substantial work for the receiver to figure out if you can help, and how.

The easier you make it for someone to know how to answer you right away, and to give you an answer with a response they can write in 2 minutes, the more likely they are to respond.

Here are things that make it easy to say YES!

Explain why you’re contacting them in particular. What is it about their work that resonated for you?

This means you should first do a bit of homework! Read their latest book/article/Substack/social media feed, and mention something specific you saw that led you to contact this human being. No one replies to a generic mass email.

Ask yourself, “What does this person want to achieve in the world? How could my ask help them do what is important to them?”

It’s easy to write an email that only contains “I” as a subject: I am so-and-so, I live here, I work here, I want this thing, [long descriptions/explanations of any of the above].

It’s worth thinking about the human being who will receive your request. What's in it for them? How can you make them the subject? [People love being the subject.] How can you align your ask with their goals? Win-win!

It’s fine to ask for a favor! People like helping others when they can. If you’re doing this, in my experience, it works best to state, “I’m writing to ask for your help/ a favor.”

Make a clear, specific ask.

Basically, make sure your message covers the classics: who, what, when, where, why. But I’d suggest this order: why [you’re contacting them in particular], who [you are/how you know them], what [you’re asking for, specifically], when/where [so they can check their calendars right then].

If it’s an event you’re asking them to join, send relevant info like other people on the program, audience background and intended learning outcome, how many are expected, online or in person, etc.

Out of the blue, “I’m interested in climate too! Let’s jump on a call to discuss” is not a clear, specific ask, tech bros from LinkedIn! :)

Keep it short!

The shorter the email, the more likely it is to get a response.

Use line breaks frequently. Make it easy to skim. Imagine they’re reading the email on their phone while waiting in line for the bus. Make it easy for them!

What have you found works for you to connect with new people? What makes it easy for you to say yes? Let me and your fellow readers know in the comments!

See You On the Internet & IRL!

Listen: I think this was the deepest dive yet into our study on what works to reduce driving in cities. Thanks, Kea Wilson at Streetsblog!

Come see me in Brussels!

I’ll be at Full Circle next Wednesday, October 3. Come say hi! Get your tickets here.

Book Recommendation: Scattered All Over the Earth, by Yoko Tawada. Just read this for my climate fiction book club and was delighted to suspend my disbelief from page 1. Beautifully observed and written, where climate change colors the characters’ lives but isn’t over-explained. I laughed out loud at some of the descriptions of Scandinavian culture.

xo,

Kim

Hi there, interesting reading. Thanks. However, I would like to propose another angle to reflection. When reading this type of approach (those who've got it right do the right thing, those doing it wrongly have a smaller/wrong understanding - I know you did not write it, but that's what the graph suggests) I get the feeling that it tends to create division more than unity, among those who are aware and a 'legion of those who ignore, or aren't capable of understanding'.

I know this has been extracted from a known paper, but a lot has happened in the almost 30 (!!) years since this paper has been published, and climate debate is far different from what it was. So I'd be a bit careful when stating, in 2023, the reasons appointed by one paper, in 1996, as the factors/causes of something.

Ultimately, a perception I think is left outside of it (it wasn't that big topic 30y ago), that is reinforced by the confrontation sought by the "8 mechanisms (...)" is the social/economic gap. These mechanisms suggest that people start from similar base points but choose to disengage, and it ignores how inequalities affect people's perceptions of realities and their priorities. An again, this approach of pointing out the misbehaviors as the only source of knowledge sounds a bit like a confrontational arrogance. The reflection I propose for us all to make is on how to engage people that are still struggling to make ends meet and to have a decent life. Putting it simply, those excluded from the benefits of globalization (and they are still majority of the world) will choose their basic (and maybe their secondary) necessities before engaging in climate acts.

That justification+ list is fascinating. And I appreciated your preferred structure for emailing people, I'll definitely be using that lol - thank you!